Credit Suisse's Capital: How Strong Is It?

Chief Executive Tidjane Thiam said recently: «Credit Suisse doesn't have a problem with its capital.» Just how well-equipped is the bank if another gale-force crisis hits and wipes billions off its capital cushion?

Tidjane Thiam’s message itself is remarkable because it shows that investors and clients are becoming more preoccupied with the Swiss bank’s solidity as the share price drops to historic lows. To be clear: the bank's capital position doesn't move with the share price.

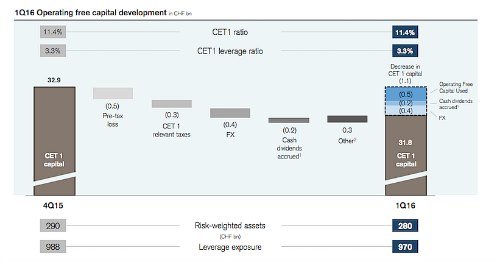

Credit Suisse’s official common equity Tier 1 capital – the most common measure of a bank’s financial solidity – was 11.4 percent at the end of the loss-making first quarter. The legal minimum in Switzerland is currently 10 percent. So far, so good.

Adequate, Not Stellar

So how strong is Credit Suisse's ability to deal with another crisis? A level of 11.4 percent is adequate, but not stellar, according to Independent Credit View analyst Guido Versondert.

One big reason why: Basel 4, a new round of capital rules – which don't even exist yet but already have a name in finance circles – expected from the Bank for International Settlements later this year. Part of Credit Suisse's efforts to heave its capital to 13 percent by 2018 is that it is widely expected that «Basel 4» to take a bite another bite out of ratios.

«Hardest» Capital

Credit Suisse's «hardest» form of capital, typically built by retaining earnings, or by raising capital from shareholders, currently stands at more than 31.84 billion Swiss francs, when using rules that will come into their full force in 2019.

The number is key – more key than a simple comparison of Credit Suisse’s capital ratio as a percentage to the legal minimum – because it illustrates the reliance on the rest of the bank’s business to deliver and for management to carry out balance sheet plans.

Cutting RWAs

The other side of the equation is risk-weighted assets (RWA), which Credit Suisse is chopping in order to prevent its business from eating away at the precious capital required to underpin riskier types of activities. The bank managed to lower its risk-weighted assets by 11 billion francs in the first quarter, a not insubstantial amount.

RWAs aren't static, and their level is the other major factor in capital. If Credit Suisse can successfully cut its risk-weighted assets, it requires less «hard» cash capital to arrive at a healthy ratio.

Dougan’s Legacy

Part of the peculiarity of Credit Suisse’s RWAs lies in its history as a derivatives house, which harkens back to the 1990s when former CEO Brady Dougan joined Credit Suisse from Banker’s Trust.

At the time, a new era of financial derivatives was emerging and Credit Suisse wanted in on it. The Swiss bank developed acumen for derivatives, particularly complex tailor-made instruments dated as long as 20 to 30 years.

These are the positions that now, halfway into their maturity, are increasingly capital-intense, says credit analyst Versondert.

Thankless Task

That means that Credit Suisse's salespeople go to clients with transactions that are 15 years into their 25 or 30 years’ maturity and shorten them – a thankless task, notes Versondert.

«There’s no revenue in it, but it’s still favorable for the bank,» Versondert says.

Derivatives are only one example of how Credit Suisse is attempting to use one side of the equation – lowering risk-intense business – to improve its capital, as opposed to stowing away earnings or even tapping shareholders for cash.

Avoid Lawsuits, Losses

Chopping its RWAs are one thing. At the same time, Credit Suisse has to make sure it is still generating cash flow from its private bank and investment bank as well as avoiding further hits to its results, like the $1 billion in losses on illiquid securitized products and distressed credit in March.

That in turn means Credit Suisse needs to be well-capitalized and solid, so that clients are happy to keep money into – hence Thiam's upbeat messages on capital. Though there is little evidence that clients have pulled money from Credit Suisse due to concerns over its robustness, this is a major worry for the bank.

Fines and penalties to amend for past scandals also factor into capital: the more Credit Suisse spends on settling lawsuits that it hasn't provided for, the less cash it has on hand to put towards capital – an issue Barclays’ analysts have previously warned of.

Gale-force Crisis?

Credit Suisse has issued a series of contingent convertible instruments on top of its «hardest» form on capital. These instruments are referred to as lower grade because they would be the first to be activated in a crisis.

The instruments are designed to automatically convert to stock should the bank drop below 7 percent and 5 percent for its hardest form of capital, or become «non-viable.»

So what would it take for that to happen? From Credit Suisse's first-quarter risk-weighted assets and «hard» capital – both moving targets – the bank would have to suffer more than 12 billion Swiss francs in losses to get anywhere near the 7 percent trigger.

Uncontrollable Avalanche

That is a breathtaking number, but it is also theory. CoCos are a new instrument developed at the urging of financial regulators, who were keen to prevent a repeat of the financial crisis.

The problem is that regulators have given little indication of how they would act in a renewed banking crisis, especially if it came alongside a broader economic crisis including the property and labor markets.

There are also few specifics of what «non-viable» entails and what would have to happen for buffer capital to be activated – which is akin to releasing an avalanche which can no longer be controlled.

So the non-conclusive answer to the question of whether Credit Suisse is healthily capitalized is, «yes, but...».