When the Brakes Fail: UBS and the Collapse of First Brands

«Bottom-up Credit Analysis»

The security is listed as senior unsecured with an irrevocable payment guarantee, leverage of 1.45x first-lien / 2.12x total, and asserts the borrower «reports earnings, holds regular management calls,» «maintains a high amount of liquidity,» and operates with «lower leverage than peers.» The slide also flags risks including default and fraud by the obligor.

The materials further highlight that O’Connor’s credit team conducts «proprietary research [that] enables bottom-up credit analysis on every obligor,» and emphasize that positions generally mature within 30 to 180 days — suggesting that any credit concern could be exited swiftly. That assurance now looks fragile: the funds remained exposed to the same borrower through at least ten consecutive «short-term» rollovers, even as Moody’s and S&P Global Ratings cut First Brands Group from B2 / B in early 2023 to CCC territory by mid-2025.

Risk Management Cascade

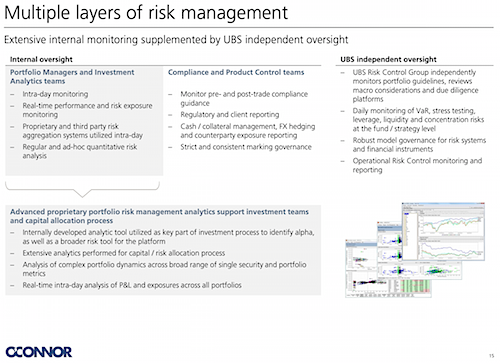

On page 15 of the presentation, UBS promises «Multiple Layers of Risk Management.» The slide lays out a cascade of processes — from «monitor pre- and post-trade compliance guidance» through «intra-day monitoring» to «regular and ad-hoc quantitative risk analysis.»

It highlights independent oversight by the risk and compliance functions, as well as stress tests and counterparty reviews. Each position, the document says, is subject to automated checks, daily reconciliations, and portfolio-level exposure limits designed to avoid concentration risk.

«Intra-day Monitoring»: January 2023 Investor Presentation by UBS O'Connor. (Screenshot: finews.com; click to enlarge)

UBS' Statement

In theory, these layers should have flagged the mounting leverage and liquidity erosion at First Brands long before default risk materialised. In practice, the language now reads like an artefact of misplaced confidence: a system presented as technologically omniscient, yet unable to catch the deterioration of the very borrower showcased elsewhere in the deck.

In its statement to finews.asia, UBS said only that «this is a sector-wide event affecting many providers of private-credit and working-capital solutions» and that it is «analysing the impact on our few affected funds.»

Questions Remain

The bank declined to address specific questions, among them:

- To whom, exactly, were the «Working Capital Finance Strategy» funds distributed – internal private-wealth clients, external institutions, or both?

- How did a supposedly self-liquidating structure remain exposed for more than two years to a borrower whose credit ratings and liquidity visibly deteriorated?

- Were risk systems really performing «intra-day monitoring» if a large counterparty collapsed almost without warning?

Busy Times for Legal

UBS Asset Management’s legal department now faces busy months ahead. The group is expected to play an active role in the US creditor proceedings to maximise recovery under Chapter 11, while at the same time navigating tense discussions with Cantor Fitzgerald, which is negotiating the acquisition of UBS O’Connor, originally expected to be completed in Q4.

Cantor has declined to comment to finews.asia: whether the exposure will affect deal terms remains open.

The Lonely Wolf

Since Greensill’s collapse, most major banks have retreated from distributing working-capital loans through investment funds. Institutions such as Citigroup, J.P. Morgan, and HSBC still finance global supply chains but now keep the risk either collateralised, securitised, or on their own balance sheets.

So far, UBS is the only major international bank publicly identified as having channelled First Brands' unsecured corporate receivables directly into investor portfolios — and into one of the decade’s largest corporate bankruptcies.

Differences to Greensill

Analysts say the distinction matters: Greensill’s products collapsed because they were fraudulent at origin; First Brands’ downfall was a case of corporate over-engineering that spun out of control — and apparently out of UBS credit analysts’ sight.

The eventual outcome for investors, however, may still hinge less on intent than on recovery values.

Staggering Silence

What they recoup will depend on how much the bankruptcy estate can realise from trademarks, production assets, and the treatment of disputed receivables within the Chapter 11 process. While outright fraud is not presumed, even a technically sound restructuring could still leave investors facing substantial write-downs — or, in a best-case scenario, recovery if asset sales exceed expectations.

While the bank’s external silence may be partly explained by the still-unclear extent of investor losses and by UBS’ current quiet period ahead of its Q3 results on October 29, 2025, the internal silence is even more staggering. It took Bloomberg to reveal UBS Asset Management’s exposure, and it is finews.asia's understanding that, so far, no internal guidance or communication on the issue has been issued to staff or portfolio teams.

Ivanovic's Problem

Internally, the affair lands at the feet of Aleksandar Ivanovic, head of UBS Asset Management and long considered a potential successor to CEO Sergio Ermotti.

The silence from both Zurich and New York suggests the scale of the unease.

Manageable Fallout

In purely financial terms, the fallout appears manageable: UBS itself is not directly affected by its funds’ performance, and half a billion dollar amounts to little more than a rounding error on the group’s balance sheet.

Yet the reputational dimension is harder to dismiss. It is neither easy nor flattering to be the only major international bank exposed to the largest US corporate bankruptcy of the year — particularly after having channelled that exposure through products sold to external investors and private-wealth clients.

Braking Systems Matter

UBS shareholders and clients alike deserve a clear answer to how this could happen, and why UBS, alone among the banks, stands out in this case.

As automotive engineers — and lawyers in that industry — know, one can never be too obsessed with the braking system. The First Brands case may once again prove that the same holds true in banking: it is the ability to stop in time that matters.

- << Back

- Page 2 of 2