Wolfsberg and the Quest for Nobility in Banking

On 8 May 2025, the UBS Wolfsberg Center for Education and Dialogue turns 50. Much has been written about the institution’s eventful history and its present-day form. Less well known, however, is how and why today’s UBS came to own this splendid estate in the first place. Exclusive research by finews.asia founder and author Claude Baumann.

In the spring of 1970, the general management of what was then the Schweizerische Bankgesellschaft (SBG, today UBS) inspected a country estate above the Untersee, on the Seerücken ridge near Ermatingen in the canton of Thurgau. Never before had the banking industry been questioned as radically as it was then, a development that shook Switzerland to its very foundations.

Speculation, huge losses, corporate crises, scandals, terrorist attacks, illicit-fund transactions, and hostile takeovers gave the decade an almost morbid air. How difficult things would yet become was something the SBG executives traipsing through the estate in the spring of 1970 could scarcely imagine.

Summer Residence, Farm, and Guesthouse

Wolfsberg documents from 1576 (Images: UBS)

The estate, called Wolfsberg, had already led an eventful life. Wolf Walter von Gryffenberg built it in 1576 as a farm. In 1732, the squire Johannes Zollikofer von Altenklingen remodelled the main building in Baroque style and used it as a summer residence.

At the turn of the 19th century, the then-owner, Baron Jean Jacques von Högger, commissioned a farm house; under Charles Parquin – a Bonapartist close to the court of ex-queen Hortense at nearby Arenenberg Castle – the property became the first guest house in Thurgau.

Wolfsberg changed owners and appearance several more times, as a current exhibition in Wolfsberg (see link) shows. A businessman named Paul Meyer-Schwertenbach bought the estate in 1938 and lived there until he died in 1966; after that, the property was left to decay.

On His Own

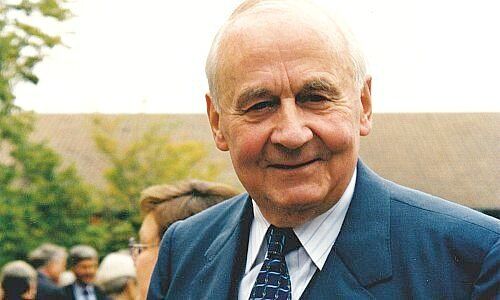

Robert Holzach, initiator of the SBG Wolfsberg (Image: private archive)

That SBG was able to buy Wolfsberg from the Meyer-Schwertenbach heirs was thanks to Robert Holzach, then a member of SBG’s general management and effectively the bank’s chief executive officer. Holzach’s cousin, Paul Holzach, had been a business partner of Meyer-Schwertenbach.

Whether the two cousins were close is unknown, but given Robert Holzach’s fascination with family history, it is likely he knew of the connection – and had been aware of Wolfsberg long before the estate passed to SBG in the 1970s.

Holzach took a gamble: he had already bought Wolfsberg – on his own and without the bank’s blessing – when he led his fellow directors through the property.

Ernst Mühlemann, long-standing Wolfsberg director and politician (Photo: Keystone)

He had staged the visit cleverly and had enlisted his army comrade from Thurgau Infantry Regiment 31, Ernst Mühlemann, then head of the teachers’ college in Kreuzlingen. Holzach rated him highly, especially after a 1963 fire had destroyed the college and the local monastery church, and Mühlemann had personally driven their reconstruction.

The Center of the Universe

During the inspection, Mühlemann depicted the Lake Constance region so convincingly as the center of the universe that Holzach’s subsequent sur place motion, as SBG jargon had it, passed instantly. To this day, the words of SBG chairman Alfred Schaefer after the presentation are quoted: «Messieurs, it’s a bit expensive, but I believe cela vaut la peine. Is there also something to drink here?»

SBG then faced a staffing problem: between 1960 and 1970, its workforce had grown from just under 4,000 to almost 10,000, nearly half under 25. Recruits were needed, and the newcomers had to be «inoculated» with the bank’s high standards.

Nobility, Refinement, a Sense of Style And Form

Wolfsberg Castle in Ermatingen, Thurgau (Photo: private archive)

Back then, many executives still lacked higher education. Holzach envisaged a training forge where the most capable people – drilled almost militarily – would be turned into universal bankers. His ambitions were anything but modest; he saw more in a banker than a mere office clerk.

«I believe in the necessity of a certain ‘nobility’ in banking. Nobility of mind, refinement, a sense of style and form: these seem dusty, outdated, at best nostalgic attributes in an era that often seeks self-realisation in pronounced nonchalance or untidiness. Letting oneself go, brushing aside the tried and tested, may be pleasanter and certainly less demanding than integrating oneself – and sometimes subordinating oneself – into structures that have shaped and still shape reality.»

Meaning of Life

Robert-Holzach-Park, since May 2025 (Photo: finews.ch)

Holzach’s idea was not merely a training centre but a Denkstätte – today we would say think-tank – for bankers:

«The banker needs a firm attitude to life to master his tasks. To understand those tasks, he must also strive to understand life’s meaning, bringing order to this complex subject through thinking and reflection.»

On 21 February 1971, at the start of Field Army Corps 4 manoeuvres, Ernst Mühlemann, then a general-staff major, crashed in a snowstorm near Rüti; corps commander Adolf Hanslin died instantly, while Mühlemann and pilot Hans Pulver survived.

Later, as Mühlemann recuperated in Ticino, Holzach wrote: «With a ‘second life’ you can’t just carry on unimaginatively.» Never one for effusive sentimentality, he simply offered Mühlemann the leadership of Wolfsberg. Mühlemann accepted and became one of Holzach’s closest confidants.

Bankers’ Monastery – With a Bar in the Coach House

Wolfsberg had to be rebuilt first. Architects Rudolf and Esther Guyer created classrooms with an auditorium, a swimming pool with a gym, and – around a pine courtyard – 120 spartan single rooms of 19 m² each.

Holzach insisted that Wolfsberg should not become a feel-good oasis but serve its educational purpose, in which modesty and moderation were key.

Today’s guest room at Wolfsberg (Photo: finews.ch)

Locals soon dubbed it a «bankers’ monastery» – even though many SBG staff enjoyed boisterous evenings in the bar-like coach house.

The official opening took place on 8 May 1975. In an age deeply influenced by the egalitarian ideologies of 1968, Holzach provocatively asked: «Can our time dispense with an elite?»

Talking About Elites

Starting from the observation that left-wing levelling made people shy away from even talking about elites, Holzach called the elite the most important institution for a society’s prosperity:

«The prime concern of the elite should be the common good.»

His speech was a ringing plea for the capable individual who consciously assumes an elite role. With Wolfsberg, Holzach wanted to create the seedbed for that role in banking.

People Under Pressure

«In every age and field, outstanding achievements by a minority have made lasting progress possible for the majority… Who, if not an elite as we understand it, could take on the same pioneering function just as well or better?»

Anyone aiming for promotion at SBG was toughened at Wolfsberg. Training mixed specialist and leadership modules with broad education in economics, politics, culture and society. Many exercises had a military flavour: people only access their last reserves under pressure – the surest way to test leadership potential.

Countless Personalities

Alexander Dubček (right), leader of the Prague Spring, 1992 (Photo: private archive)

Besides lectures, seminars featured group discussions on political, cultural, and social issues. Role-plays simulated, for example, how a branch manager should respond to a demo outside his bank. Media training brought in hard-nosed tabloid journalists to grill staff in fictitious interviews.

Mühlemann also turned Wolfsberg into an international meeting place, inviting entrepreneurs, politicians, and artists – from Helmut Schmidt, Alexander Dubček, and Mikhail Gorbachev to Franz Josef Strauss.

Conversion and Expansion

In the early 1990s, SBG’s leadership under Robert Studer criticised Wolfsberg for not keeping pace with the end of the Cold War, globalisation and the Americanisation of finance. Ernst Mühlemann retired in 1992; the concept was revised.

Between 2005 and 2008, the centre was remodelled and expanded, including a new accommodation wing that met the highest comfort standards – the asceticism Holzach prized disappeared entirely.

International Orientation

Entire complex from the air (Image: UBS)

Today, the «UBS Center for Education and Dialogue» is a UBS subsidiary. From a «bankers’ monastery» for SBG management, it has become an internationally-oriented venue that mainly hosts events for other firms and UBS clients, and now provides far less in-house banker training.

The roughly 30 annual events of the Wolfsberg Dialogue Program put UBS clients center-stage, create exclusive networking, and connect people. Its three thematic platforms – «Economics», «Politics», and «Passion» – align with global megatrends and UBS’s strategy.

These exclusive, invitation-only events give clients the chance to meet experts, take part in cutting-edge dialogues, and exchange ideas with leading figures.