An evening out with friends has the potential to teach us a lot about investment decisions. Behavior in the capital markets shares many similarities with our party-going habits, writes LGT investment expert Thomas Wille.

By Thomas Wille, Senior Investment Strategist at LGT

Nobody wants to leave a great party too early and risk missing the best part of the evening – and as a general rule, parties should be high-spirited affairs. But if you want to be able to enjoy the next day without any regrets, choosing the right time for your exit is key.

Sometimes, however, this is easier said than done: the longer a party lasts, whether at a friend’s place or on the stock market, the stronger the feeling of intoxication. Rationality disappears, sometimes to such an extent that people lose control. There are various possible causes for this, but the effect that comes as a result is always the same: a hangover.

Exiting the Party: How Soon Is Too Soon?

The easiest solution would probably be to leave the party sooner rather than later, and in doing so, avoid the hangover – but this is exactly the dilemma faced by all partygoers: they do not under any circumstances want to find out the next morning that they missed the actual highlights of the evening. If we apply this scenario to stock markets, we see a very interesting, and at the same time unexpected, pattern.

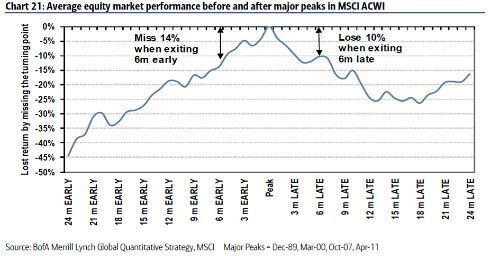

Using the average stock market performance prior to and after a peak, the chart illustrates what happens to returns if investors sell too soon or too late. If market participants sell six months before the peak, they miss out on an average return of 14 percent. This is hardly surprising, because major returns are always lying in wait during the late stages of an equity bull market.

If, on the other hand, I only exit the market six months after the peak has been reached, I suffer an average loss of ten percent. If I then add to that a three percent dividend yield, staying invested for longer could indeed prove worthwhile – 14 percent opportunity costs compared to a seven percent loss since the end of the equity bull market. That is one party that should not be left too soon! But is it possible to predict the end of a bull market?

The Condemned Live Longer

Behavioral economics can be very helpful here. The more capital market participants are heralding the end of the bull market and pointing to the dangers of late-cycle behavior, the greater the likelihood that the upswing is not yet over. In 1999/2000, only a few market participants spoke of a downturn. Some even propagated that this time around, everything was different.

Even shortly before the outbreak of the financial crisis at the end of 2007/beginning of 2008, there were hardly any investors who were predicting an end to the bull market.

So how does this apply to the current situation? For almost 12 months now, people have continuously been trying to predict the end of the nine-year bull market. Behavioral economics shows that the expression «the condemned live longer» also applies to investment behavior. But how should investors conduct themselves in a late-cycle bull market?

The Later the Evening Goes...

The US stock market has been trending upward for nine years and the MSCI World Index shows a similar price trend. The S&P 500 has risen from 666 points to over 2600 points. The big price gains are likely now already in the past, or in other words: this party has already gone well into the night. It is precisely during this phase that investors should become very selective and have a strong grip on their risk budget and their setback potential.

Equity investors can sharpen their focus by limiting their selection to a number of sectors or countries. This enables them to benefit from late-cycle industries such as the energy sector, for example. They should also tend toward reducing the risk budget and realize gains during periods of strength.

Party Planning for the Cool-headed

Which tools exist for reaching the most rational decision possible? Investors should firstly define their maximum loss threshold, as of which they will leave a stock market party, beforehand. Secondly, they should set a target price, from which point onward, they will start to realize their gains and in doing so, reduce risks.

Finally, they should also bear one thing in mind: do they want a bird in the hand or two in the bush? You can’t have both in the stock market either.

Thomas Wille is Head Investment Strategy & Communication of the LGT private banks in Europe. He studied finance at the University of St. Gallen and has worked in financial markets, specifically in investment strategy and asset allocation, for over 20 years. In addition to fundamental analysis, he also places a strong focus on how behavioral finance factors influence capital markets.