Popular reform cannot be the preserve of populists alone if global finance is to regain legitimacy, Anne Richards, CEO of M&G Investments, writes in an exclusive essay for finews.first.

finews.first is a forum for renowned authors specialized on economic and financial topics. The texts are published in both German and English. The publishers of finews.com are responsible for the selection.

Instead of political convergence, we have witnessed growing fragmentation across many Western democracies over the past decade. There has been a polarisation of political views in response to the financial crisis and its fallout. Voices that oppose the economic system, and the role of global finance and international trade within it, have grown louder.

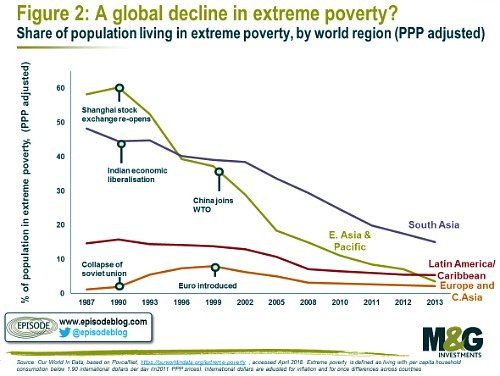

Yet there are risks that proposed solutions could mean «throwing out the baby with the bathwater». Unless many widespread concerns are successfully addressed, the global economy’s ability to create wealth and lift hundreds of millions out of poverty could increasingly come under threat – leaving us all worse off in the long run.

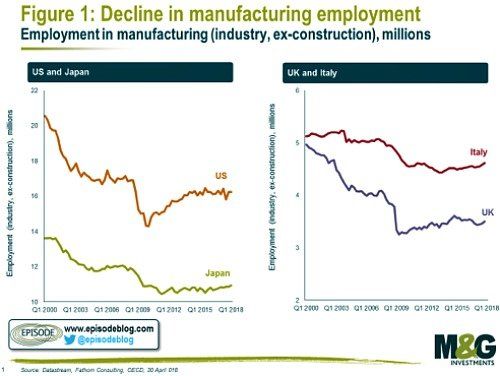

The financial crisis accelerated structural forces that were already disrupting the established socio-economic order in parts of the West. A lack of global competitiveness in many traditional industries had already consigned millions of workers to structural unemployment.

The fallout from the crisis destroyed jobs and dented confidence in the global economic system. Slow growth hindered the recovery, and many of the new jobs that have been created in developed market economies are casual or temporary in nature.

The rise of a disenfranchised «precariat», battling low wages, high living costs and economic insecurity, has been seized upon by many politicians, eager to capture the energy of their frustrations and ride the wave to power. Some have succeeded at the polls, often with an anti-global agenda.

«It's unlikely that economic nationalism will lead to the recovery in living standards»

Yet unravelling the agreements that have underpinned decades of strong economic growth around the world could be highly detrimental, including for many of those embittered by globalisation.

The chart shows the apparent decline in extreme poverty over the last thirty years and the background of increasing globalisation. Assessing a relationship between the two is no doubt over simplistic; not only do we have the problems of correlation and causation, but there are real problems in collecting poverty data.

However, it is clear that we need more than just rhetoric to make a case against globalisation. Trade is not a zero-sum game and it is unlikely that economic nationalism will lead to the recovery in living standards that some argue, with a meaningful risk of unintended consequences.

Many lost jobs will never return having been replaced altogether by robots. Moreover, as consumers, many in the developed world benefit from cheaper imported goods. Finally, what about the detrimental impact of economic nationalism on foreign workers?

- Page 1 of 2

- Next >>