Will next year’s automatic data sharing arrangement render tax inspectors obsolete? Hardly, an expert tells finews.asia. He reveals what new methods tax authorities have up their sleeve to root out tax dodgers.

From next year, Switzerland will begin handing over data to partner nations on offshore accounts held in Swiss bank accounts. In theory this means total transparency.

In reality, tax authorities are stymied by Europe’s pastiche of dozens of national tax regimes and laws, Ernst & Young’s Hans-Jochen Jaeger told finews.asia an in interview. Instead, investigators will resort to unconventional measures to nab offenders, Jaeger says.

Mr. Jaeger, how are statisticians going to find tax evaders?

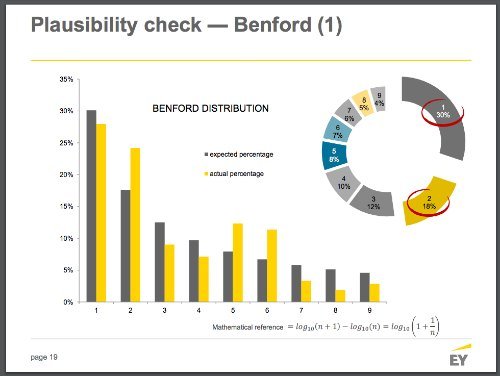

Tax authorities are about to receive thousands of sets of data, but they want to save their limited resources for the cases where they believe they will find tax offenders. The first thing they will do is program their computers in a way to look at something called Benford's law.

What is that?

Take a set of data which are interconnected in some way and not totally random – like a tax declaration. If you only take the first digit of each number, how many times do the numbers 1 and 2 occur? The number 1 will occur as the leading number in about one-third of all cases, and the number 2 as the first number will occur in about 18 percent of all cases (slide below provided by EY).

Thus, I can conclude that at least half of all the numbers will begin with either 1 or 2. You can apply that to pretty much any set to interconnected numbers: we now know that in some penal cases records were actually cooked up in a way that made numbers look legitimate according to Benford's law.

Back to tax returns, if the actual distribution of numbers is different, it doesn’t necessarily mean something is wrong, but it probably warrants the tax authority taking a closer look.

Why can’t tax authorities just match the data they receive with their own database?

The OECD’s common reporting standard doesn’t adhere to any national tax law but requires the data to be interpreted according to the tax laws of the sending country, i.e. the country of the sending bank. However, the receiving tax authorities will «look» through their glasses, meaning that they will interpret all payments according to their tax law.

Payments from structured products, repayment of capital and securities lending are taxed in very different ways; by definition, these two reports will never be the same from one country to another. That might come as quite a frustration to tax authorities, who had thought they could match data from the Common Reporting Standard with data from the taxpayer’s tax declaration, like the U.S. does under a common tax ID like in the U.S., but they now realize they will never be able to do so.

What they can do is – going back to Benford – check the plausibility in a first instance. And the really interesting thing for the tax authority is they can analyze the data.

Analyse it for what?

In the future, the tax authorities will try to look for correlations, and not causalities. Of the hundreds of thousands of data points that, for example, Germany is about to receive from Switzerland, the first thing investigators could do is plot assets under management against income. Every statistician will try to find a correlation between the two, and then define a standard deviation.

Within these, 95 percent may not be of interest to them. What is of interest though are outliers: clients who have huge assets, but less income than expected. Tax authorities will not only do this with just one correlation; they will try to several others to support their findings.

What sort of links would ring alarm bells?

One that is linked to a high probability of evasion is foreign shares and withholding tax on dividend income, which can be reclaimed under double-tax agreements. Legitimate investors would like to reclaim that tax, but to do so they have to disclose their identity – no tax evader would usually voluntarily do that.

So tax authorities are likely to look at portfolios with a lot of foreign income, but no reclaimed withholding tax. They can see the recovered withholding tax from the tax declaration and try and match it against the assets under management from the automatic exchange of information, so they can connect these data.

Any other detective work that tax investigators will employ?

They might be inclined to look at asset management fees. These tend to be low in the beginning, then increase, but usually there is a tipping point where the client has brought on a sizable amount of assets and tells his bank or insurance company that he or she wants a rebate. Tax authorities will try to look at cases of proportionally more asset management fees reported than you might expect given the level of assets under management. Even more interesting to them is a very low level of assets, while still reporting a high number of management fees.

Which authorities are already doing this?

(British tax authority) HMRC has program called «Connect» which matches data points from taxpayers with the land registry, utility providers, and so on. They connect all this data to see whether it fits together, and if it doesn’t, there will be some scrutiny there. Around 30 sources are said to be going into the program, including social media - as long as a source publicly available, they will tap it.

HMRC is already screening all tax declarations to see if they fit Benford’s law. Tax authorities are also considering using the same software employed by the ICIJ to sort through the Panama Papers, called Lincurious. Using this software, you can tap through an entire database to interconnect one person or company and legal entities.

The computer capacity is there, the storage capacity is there – storage doesn't cost anything these days.

This sounds quite Orwellian, really.

My last information was that the entire data under the OECD’s common reporting standard is stored on one server in one EU country. If you were a hacker, you would probably want to get access to this one server because everything that has been labelled «strictly confidential» and «for internal purposes only» is on there; past history has shown that these data is particularly prone to data security breaches.

There is also the politically touchy topic of more sinister countries that have regimes that are not compatible to our understanding of democracy. If those authorities see that a lot of their taxpayers are investing in other countries, it can easily be translated into a kind of political pressure on both, their taxpayers and the other countries.

Speaking of Orwellian tendencies, I believe there will be a fundamental shift of power and possibilities from the taxpayer to the tax authorities in the coming year as, over time, the latter will receive data to analyze and to even carry out some «predictive» analytics.

Hans-Joachim (Jochen) Jaeger is a partner specialized in tax at EY's financial practice in Zurich. Previously, he worked as an options trader, at a German private bank, and as a tax expert at consultant Andersen and private bank Julius Baer. Jaeger, who holds a PhD in tax law and a Masters degree in business from St. Gall, has been with EY since 2003.