Forget Home: Banking's New Nomads Will Work From Anywhere

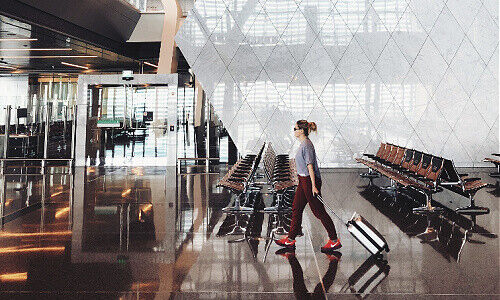

The pandemic is shifting thousands of financial services out of the city centers. The new employment model for bankers is not working from home – but from anywhere.

Want to or can – that's the question: Credit Suisse's top markets banker Brian Chin made clear last week why he wants traders and investment bankers back after one year out of the office due to Covid-19. The American banker is afraid of Zoom fatigue and burnout accompanying the work-from-home routine.

The other view is that some financial services workers have little to no desire to return to packed office spaces: workflows, processes, and channels have quickly been fully digitized, and employees have far more flexibility in planning their day including childcare than until now.

Seldom-Seen Office Guest

A Swiss finance executive was hired to run the Zurich office of a U.S. wealth manager last summer, but hadn't actually worked on-site in the first nine months, he told finews.com. He met and works with his team only virtually thus far – and would give anything to change that, he said.

That's not on the cards anytime soon: most big financial services employers in Switzerland as well as abroad are some ways off from bringing back anything but skeleton staff to physical offices. The slow roll-out of the Covid-19 vaccine is one factor, but the pandemic's more lasting impact on working models is the bigger picture.

Outdated Office Models

The shift represents one of the biggest changes for financial services – on the order of the introduction of personal computing in the workplace, or the «Big Bang» under Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s. The catalyst this time isn't political or industry-specific, or even changing client needs, or deregulation of financial markets.

More simply, it is the recognition that existing working models aren't apt anymore: few bankers can or want to work the same way as before the pandemic. This means seismic changes for financial services players and their employees, but more broadly for infrastructure and technology, real estate, and oversight.

Hollowed-Out Centers

The U.S. has led the way: Wall Street emptied out during the first wave of infections in the U.S., with many bankers heading for balmier climates such as Florida or Arizona. The fear at the time that bankers wouldn't return to Manhattan has come to bear.

Not just the fair weather, but structural reasons like lower taxes as well as ease of travel between Florida and New York for short-term client meetings is a major factor. Goldman Sachs is reportedly planning to shift part of its asset management unit's staff to the Sunshine State – home to many of America's super-wealthy. New York state's planned wealth tax is an additional impetus for some to flee.

Mountain Hideaways

The Swiss equivalent is fleeing for the hills: Swiss financial heavyweights including CVC co-founder Steve Koltes and ex-Falcon Chairman Christian Wenger are among the potent backers spending millions to entice disgruntled city natives to a popular Swiss alpine valley to work. The heart of the Lord Norman Foster-designed project is scheduled for completion next year but the project is already popular enough to open a pop-up location in December.

Bramble Ski founder Natasha Robertson was the first to offer luxury chalets, including meal service, in hot spots like Zermatt, Méribel, and Verbier. Founded in 2005, the boutique is enjoying a boom in long-term bookings thanks to the pandemic. «Staying over in your own so-called bubble is booming,» Robertson told finews.com.

Clients Absent From Offices

Some London-based bankers have decamped to warmer climates – Andrea Orcel is now based in Lisbon. For Swiss-based financiers, the alps are a more natural retreat zone. «We haven't had any clients in our office for the last 12 months, but at the same time higher revenue than the year before,» a Zurich-based wealth manager told finews.com, speaking from Grison, where their firm is scouting office space.

«Working from home» is increasingly making way for «work from anywhere,» and getting backing from even the industry's largest and most traditional players. HSBC, for example, wants to give up more than 40 percent of its office space worldwide, and doubtless, others will follow suit, hollowing out once-bustling financial capitals like London and Zurich.

Abandoning Outskirts

However, the drain will reveal dramatic differences between inner city and outskirts, as realtor Jones LaSalle noted in a recent study. Demand prime office space in Zurich is due to remain intact, according to the realtor, while outlying areas including Opfikon or Glattbrugg – where big banks have moved thousands of employees in recent years due to more and cheaper space – are already up to one-third empty.

The trend won't stop, especially as newer technology firms encroaching into banking are eschewing splashy central office space. The innovative start-ups are, of course, far more acclimatized to working virtually and entrusting their data to cloud service providers, for example. Flat hierarchies help make these fintechs far more attractive to graduates than traditional banking – and mobility is a huge part of the draw.

Far-Reaching Consequences

This all means death by 1,000 cuts for once-powerful financial centers in favor of a cloud-based workplace accessible from anywhere, be it Grison, Lisbon, or the Côte d’Azur. This has far-reaching consequences not just for countless properties and physical infrastructure.

The travel, food, and hospitality industries have long benefited from the financially potent clientele that frequent financial centers. In sum, it also means less tax revenue for havens like Zurich, a city which has grown prosperous in large part due to its reliance on finance as well as the related industries the tourism brings.

Capital Keeps Flowing

The pandemic workplace shift is accentuated by political turmoil affecting financial centers like Britain's departure from the European Union, Hong Kong's democracy protests, or even the unclarity over Princess Latifa, the daughter of the ruler of Dubai, illustrate how fickle the fates of big money cities are.

Big investment banks have pulled staff out of the City of London in favor of Madrid, Frankfurt, Luxembourg, or Paris, while in Asia institutes are increasingly favoring Singapore, Tokyo, and Seoul. The larger picture is «come and go as you please» – mirroring the flow of capital in places of least resistance, best price, quickest execution.

Reporting by Claude Baumann and Samuel Gerber; Katharina Bart contributed.