A UBS foundation is the investor in a high-yield bond linked to learning development of young girls in Rajasthan, India. The bond is backed by a charitable foundation with links to a prominent hedge fund titan and activist investor, finews.ch can reveal. The idea of the wealthy making a profit on improving conditions for the disadvantaged is controversial.

The Swiss bank is part of a public and private sector push for more effective aid programs in key areas like health, education, and infrastructure, a model that UBS is interested in because philanthropy is a key pitch for the wealthy clients it deals with.

Both development organizations as well as financial firms like UBS are backing a new type of charity which measures the results of development aid and pays a return based on how effective it is. In short, making a profit while making a difference.

First DIBs

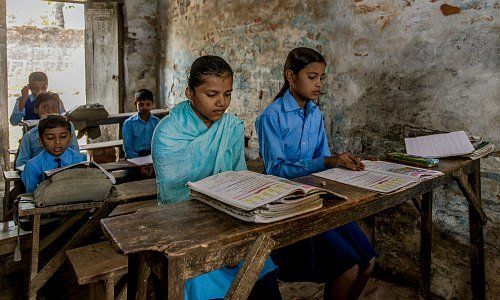

The Swiss bank is one year into a three-year development impact bond, or DIB. Optimus Foundation, a philanthropic entity within UBS, put up $300,000 last year to a program meant to help children and especially girls in Rajasthan, India who aren't attending school to learn to read.

The better the girls’ school results are, the higher the coupon paid to the UBS foundation – plus the bond’s original principle. In this particular case, the bond pays out up to 15 percent at maturity, funded by a charity, if after its three-year duration the girls' literacy has improved.

With the entirety of Switzerland's government bond yields in negative territory and interest rates at historic lows, this represents an almost unprecedented rate of financial return.

Hefty Payout

One year in, UBS' foundation would have earned 40 percent of its initial investment back, because nearly half of all out-of-school girls have since been enrolled in school and have achieved one-quarter of learning targets set out for them.

A charity founded by prominent hedge fund activist Chris Hohn is the bond issuer in this case, or so-called «outcome payer». Hohn and the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, or CIFF, are early adopters of results-based charitable giving, or ensuring «performance» on the ground matches the checks written.

Prominent Critic

While UBS has been an outspoken advocate of using private wealth to help public sector efforts, the idea is controversial in charitable circles. «The Brookings Institution», a leading Washington think-tank, cautioned about the potential conflict in linking development aid to securities sold to wealthy investors.

«If an impact bond is designed to improve outcomes for individuals in the lower-income quintiles through non-state providers, the stakeholders must ensure that the impact bond does not exclusively finance for-profit non-state providers that cater to the wealthy,» the think-tank wrote in a January study.

Governments, NGOs as Bond Issuer

The model is meant to make donors, non-profit agencies, and governments more efficient in trying to end poverty, fight inequality and injustice, and tackle climate change – part of UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for 2030. It is meant to unleash vast reserves of privately-held cash in the fight against global problems.

UBS’s first bond with CIFF, the charity, is a test case. In future cases, impact bond issuers could be non-profit organizations, such as large endowments, or governments. This raises the specter of wealthy UBS clients receiving impact bond payouts from, for example, governments in developing countries such as India.

The Wealthy Earning from the Poor

The idea is controversial. In the UBS case, governments should be taken to task, according to an academic.

«It's based on the premise that school education cannot be done by governments, but only by micro institutions, and that you can improve accountability and achieve targets with rather weak measurements and monetary incentives,» Jayati Ghosh, a professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, told the «Thomson Reuters Foundation».

15 Pct Bond Return «Just Wrong»

Part of Professor Ghosh’s objections stem, like the Brookings Institution’s warnings, from the fear that the bonds are simply too lucrative compared to other investments.

«There is definitely a gap in education, but to think you can fix it with a 15 percent return is just wrong. The government is completely reneging its responsibility,» Ghosh said.

UBS Counters

The head of UBS’ foundation, Phyllis Costanza, argues that what is estimated to be a $2.5 trillion annual hole in funding the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is one of the most powerful cases for private sector intervention.

«We need to come up with creative ways to bridge that funding gap,» she says.

She also cites low U.S. rates of charitable contribution abroad, where a mere 5 percent of philanthropy goes overseas.

«How can we encourage people who live far away from some of these challenges to invest in them?»

Goldman Sachs Social Bond

The transparency and accountability of impact bonds, where progress towards development goals is regularly and typically independently measured, is another case for them, Constanza says.

To be sure, DIBs and SIBs, or social-impact bonds like a controversial one invested in by Goldman Sachs to help underprivileged preschool children in Utah, are a nascent market. UBS will earn up to $45,000 in interest, on top of getting its initial $300,000 principle back on its Indian bond investment.

Those are modest absolute numbers. But the appearance of UBS, the world's largest private bank, in the impact bond market is a sign that the bank expects major demand from its millionaire and billionaire private clients. Controversy over the bank's role in the development debate seem inevitable.