Three major crises in the less than twenty years shook the foundations of the Swiss financial system. Three lessons however are enough. Now, Swiss financial markets must not be lulled into a false sense of security, writes Rudi Bogni.

This feature by our guest author Rudi Bogni is the first contribution to our new section finews.first. It is a forum for renowned authors specialized on economic and financial topics. The texts will be published both in German and English. The contributions appear in cooperation with Pictet, the Geneva-based private bank. The publishers of finews.ch are responsible for the selection of the contributions.

I cannot offer a totally independent view. For about ten years, I was an insider. I joined Swiss Bank Corporation in 1990 to head the then loss-making London office. Those were exciting days: SBC bought control, in rapid succession, of O’Connor, a Chicago-based derivatives specialist, Brinson, a successful Chicago value asset manager, and then Warburg, the mythical U.K. merchant bank. In 1997, I moved to Switzerland to head the Private Banking division of SBC and then for the newly merged bank UBS.

I remember giving an interview at the time explaining how vital it was for Swiss private banking to defend its prime position in the world by moving rapidly to further the technical competences of its bankers, by connecting to society’s better values and by establishing domestic booking centres in other key countries from which one could offer tax-effective investment products. The article was not well received.

«Despite my pragmatic acceptance that the days of banking secrecy were numbered already then, I always believed in its fundamental principle.»

I proceeded nevertheless to «walk the talk» and two of the things I am most proud of were the roll-out of a major graduate management training programme for wealth managers and, at the urge of my colleagues and with the support of Marcel Ospel, chairman at the time, the establishment of the Optimus Foundation.

Despite my pragmatic acceptance that the days of banking secrecy were numbered already then, I always believed in its fundamental principle. I am still convinced that defeating tax evasion is only a secondary intent of the attack on banking secrecy worldwide. The primary historical motivation has always been the control of the citizen by the state, tax being only one of many aspects of that complex relationship.

For the avoidance of doubt, I maintain that citizens should honestly pay tax as part of the social contract. However, more than once I openly disagreed in public with those politicians who claimed that paying taxes was a universal moral obligation. Was paying taxes in Nazi Germany moral? I rest my case.

«Swiss Banking privacy and secrecy have deep cultural roots.»

Most people think that Swiss banking secrecy dates back only to the Banking Act of 1934 and its reaffirmation in 1984. That is incorrect: the great council of Geneva required bankers already in 1713 to maintain client confidentiality unless the City Council required otherwise. Banking privacy and secrecy have deep cultural roots.

Today the Swiss financial markets, of which banking is a very significant part, are in good health, despite the undermining of banking secrecy, but with privacy still a core value.

Of course, the financial sector’s balance sheet is still huge in relation to the size of the country’s balance sheet and GDP, but gold-plated capital rules have forced the equity base of the sector to revert to the more prudent ratios of the past and even exceed them. The remaining and unavoidable vulnerability is the need of access to the U.S. dollar markets.

After World War II, the central banks of Germany, Italy, Japan and Korea were granted U.S. dollar swap lines to allow them to revive the domestic economies. Switzerland did not need such extensive support, although, interestingly, funding to German banks had to go through a so-called «Swiss pool» to window-dress the maturities of their liabilities.

In another global financial crisis, even Switzerland may require continued access to U.S. dollar and, less significantly, to euro markets through swap lines. This is the unavoidable risk of a small country playing in the global markets. Moreover, every day the Swiss financial institutions need access to clearing and settlement systems of both the dollar and the euro.

«Despite the crisis, Swiss investors have not lost the taste for financial innovation.»

This is why for a globally integrated economy and financial system unfettered sovereignty is an oxymoron. The good state of the Swiss financial system today is due to the increased technical competence of bankers, insurers, members of the exchanges, asset managers and independent advisors, otherwise called intermediaries. This improvement was built on the solid base of Switzerland’s main assets: the certainty of the law, the resilient institutions, the common sense of direct democracy and, after the financial crisis, the recapitalisation of the main players.

Despite the crisis, Swiss investors have not lost the taste for financial innovation, such as in the field of insurance-linked securities and their related funds. In the last twenty years there have been, however, moments of major disorientation.

I remember very well the shock and surprise of both the financial sector and the general public at the accusation of Jewish organisation and the U.S. government that led to the so-called «holocaust negotiations».

«The main purpose of the campaign was to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive.»

Switzerland had been a front-line neutral country in the war and had accepted not only Jewish fugitive capital, but also Jewish refugees. Furthermore, it had kept impeccable records of all deposits and investments. Swiss banks could perhaps be blamed for having been sometimes bureaucratic and inflexible in releasing funds, but the records at least were there.

Once I had a heart-to-heart conversation with a leader of a Jewish organisation. I asked him why he was concentrating his attack on Switzerland and not on the other two major centres of capital flight from Nazi Germany, London and New York.

After all, in the state of New York, all dormant accounts were confiscated for the benefit of the fiscal coffers of the treasurer after only five years and no records remained. He told me that all these were irrelevant details; the main purpose of the campaign was to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive.

The matter was eventually sorted out, not without major soul-searching and loss of heart at what some perceived as unjust treatment at the hand of the U.S. government, which, after all, had been a partner of Switzerland in the settlement of the Interhandel deal.

«Swiss banks, as banks all over the world, had accepted to become de-facto fiscal agents of the U.S. government.»

In the second major debacle for the banking system, Swiss politics and diplomacy came out more confused and battered. Swiss banks, as banks all over the world, had accepted to become de-facto fiscal agents of the U.S. government. U.S. banks would be never allowed to be fiscal agents of a foreign government, but realpolitik is made of such asymmetries.

I was then no longer directly involved in Swiss banking, but it appears that a number of Swiss banks may have thought that, despite such a role, it was business as usual. As one could expect, the U.S. came down hard on this alleged non-compliance with their extra-territorial reach and the consequences are still being dealt with as I write.

«Complete the ingredients with excessive liquidity and share buy-backs and you have the perfect toxic mixture.»

The third major crisis was the global financial crisis. Its seeds were sown long before the subprime mortgage problems became apparent. Accounting reform had made financial companies’ balance sheets inscrutable to the average person and, worse, to the average board member.

Add to that the emphasis on risk-weighted assets as opposed to gross assets and it is simple to understand why bank boards missed the dramatic increase in leverage by many banks. Complete the ingredients with excessive liquidity and share buy-backs and you have the perfect toxic mixture.

The fact that the banking system and the entire financial system survived such a crisis has been seen as a miracle orchestrated by the Fed and the U.S. government. One can however interpret it also differently: that at least the Swiss system was solid enough and the choice of assets not so disastrous as to bring it down, despite twenty years of global political attempts to use debt as a substitute for productivity increases and as a way to deal with over-extended electoral promises.

Three major crises in the less than twenty years shook the fundaments of the Swiss financial system. Three lessons however are enough. The margin of error declines with every crisis. The Swiss financial markets are efficient and can cope with the expected over-reach of regulation, but they must not be lulled into a false sense of security.

«Financiers are paid to take risks and they will make mistakes.»

Bankers, insurers, members of exchanges, asset managers and independent advisors must rely on their own judgment and integrity. Ticking boxes and an ever increasing the list of PEPs (politically exposed personalities) cannot be the beginning and the end of financial business.

Financiers are paid to take risks and they will make mistakes as Sergio Ermotti, CEO of UBS, was recently quoted as saying to his colleagues.

Integrity is part of character and the culture of the country still holds it a core value. Judgment is something that one develops with experience, by thinking, analyzing and acting. It is not something that you can acquire simply by exploiting position rents or endowments.

Switzerland is well positioned, but political, diplomatic or management disorientation could still threaten that privileged role in global finance.

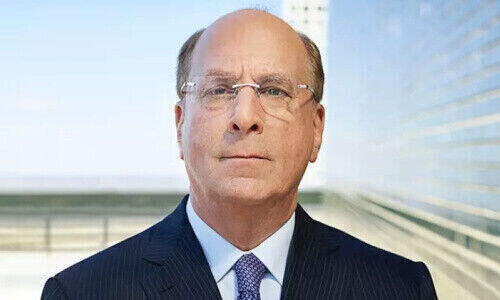

Rudi Bogni, an Italian citizen, 68 years old, resides in London and Basel. He is chairman of Northill UK, a director of Waypoint Capital Holdings and a trustee of the Prince of Liechtenstein Foundation and of LGT. He is also a member of the Governing Council of the CSFI (Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation), a member of the Advisory Board of Oxford Analytica and of the Council of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. He is a member of the Securities Institute, of the London Mathematical Society and of the Vereinigung Basler Oekonomen.

He started his banking career in the early 70’s with the Chase Manhattan Bank, was Group Treasurer of the Midland Bank and finally CEO, Private Banking of UBS. In the past, he was also SID of Old Mutual plc, a trustee of Fondazione Bruno Kessler, an independent director of Moody’s (UK, France, and Germany) and a trustee of Common Purpose Charitable Trust.